Ribbed Routes

G.R. Iranna: The Peace Project

There are some pressing issues of our times that require our address. Questions of peace and the prevalence of violence in the form of dissent, any dissent, press on our consciousness and demand a response. The reason I have titled my essay ‘The Peace Project’ is because I see and I would like to encourage others to see this all sculptural show by Iranna as a concerted and concentrated address of what should be society’s goal in the coming years, to work towards peace and harmonious coexistence. It is not naïve to imagine this as a goal that we should place at the forefront of our plans and it is not a goal achieved through individual action but one attainable through collective enterprise. There have been moments in history when the call for peace has gone around and captured the hearts and minds of people, now is another such time.

This body of work, as you will see is about depair but it is also about hope, for both nestled together in Pandora’s box.

Peace and Pieces

The anatomy of peace is figured as the reclining form of Parinirvana Buddha. The aspect of Buddha attaining freedom from the cycle of life and death is envisioned by Iranna as the moment to desperately claim the body that is a symbol of peace and create an allegory of our troubled times. He studs Buddha’s peaceful reclining body with surgical metal clamps used to hold broken bones in place as they mend. The sleeping Buddha shows no discomfort that such a physical situation would cause, his sleeping face in repose displays a calm, beatific smile, the folds of his gown are perfectly symmetrical and his hand rests gently on the round pillow.

The Parinirvana Buddha is a familiar icon in the visual history of mankind. Iranna has cleverly sandblasted the fiberglass sculpture to resemble the monumental sculptures of ancient and medieval art history. Buddha sleeps on a bed of three rows of metal trunks, each imprinted with the words ‘Tool Box’. These are obviously a workman’s item and are meant to relay the everydayness of the trunks, in contrast with the ‘spiritual otherness’ of the sleeping/ mending Buddha.

Iranna tells an anecdote that further enforces this idea of the ‘significant commonplace’, an idea that is repeatedly manifest in the exhibition. When the artist left his hometown to travel to Delhi as a young man, his luggage was just such a metal trunk. The metal trunk has been poetically cast through the history of Indian cinema to represent a young person’s journey of hope and ambition. Here perhaps it is again the vehicle of hope but as a collective, as well as individual, desire.

Garden of dead flowers

An act often contains within it the motivation to evoke a response. A violent act leaves in its wake anger, confusion and the desire for revenge. The revenge may be equally violent (which some may consider just, such as the American War on Terror) or it may take the recourse of bringing the perpetrators of the crime to justice, such as India is attempting with Pakistan after the November 2008 Mumbai terrorist attacks. For many of us citizens of India it is the civilized course of action, though long-winded but it doesn’t lessen the incomprehension many of us have of this modern form of cross-national, cross-communal urban guerilla warfare.

Iranna’s installation tries to make some sense of this act and come up with an adequate personal and emotional response to the horror. The variable sized installation consists of several partially burnt wooden padukas and a vehicular siren, the kind atop police cars and ambulances. Padukas are an ancient form of footwear worn most commonly by Hindu and Jain holy men and women. They reflect the principle of non-violence by minimizing the risk of trampling animals, insects and vegetation. They also serve as venerable objects of votive offerings. Their haphazard abandonment in the artwork symbolises, quite simply, the abandonment of the principle of non-violence as a life path.

The siren is the quintessential sign of danger or an emergency. Its relentless activity is unnerving, as though the danger is constant and all-pervasive. The scattered mismatched padukas also bring to mind photographs or video clippings we often see in the aftermath of a public attack but perhaps pay little attention to. These scenes are often characterised by discarded objects, dismembered body parts and mismatched footwear of the victims and stand-in for the corpses that were.

It is a poignant work, quietly forceful, internalising the discourse on contemporary violence and spiritual teaching.

Heartbeat of a Revolutionary Object

A beautiful wooden charkha lies on an ugly metal hospital stretcher. It is connected to a sphygmomanometer and a little device that records/ creates its feeble heartbeat. It is a forlorn picture and a desperate sound…

Best known for its association with Mahatma Gandhi , the charkha (etymologically related to the chakra) was both a tool of self-sufficiency and the symbol of the Indian independence movement and adopted as the central icon of the flag of the Indian republic. Such a proud lineage ends in such a sorry state… and yet there is still optimism as there is still the heartbeat… will the charkha’s pitiable state spur us to attempt at non-violent paths of affirmative action? We are left with this final question.

Wall Mounted sculptures in Glass Cases including I Lost the Taste of God and If I Wear a Stone

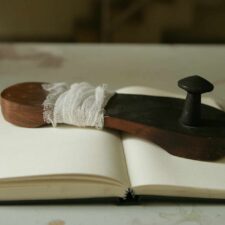

In a group of work padukas are combined with a number of other objects to reinforce this message of the danger of disenchantment: the bandaged slipper placed on a book points towards the lack of respect of knowledge and wisdom; there are scissors and other implements that point to something broken or damaged. The most striking for me in this group is the sculpture of an old fashioned hand juicer/ grinder. Tiny wooden padukas are fed at one end and what comes out is a red pool of, what we can only conjecture, blood.

Placed as they are in glass vitrines, do they suggest that the principles that these symbols represent are old and outmoded? That they are to be studied dispassionately? Does it suggest their lack of relevance in contemporary times? That is part of the challenge Iranna has taken up in this exhibition, to wrest the meaning from shelved symbols and objects and situate it again at the heart of a ‘good’ or better way of life. And yes it is by no means a small insignificant task for it requires him to engage with the truly difficult situation of today, respond to them and through that response wrest an engagement from the audience.

Still Saddled

This work is somewhat different from the message and medium of the other works detailed above. It harks back to Iranna’s previous sculptures in recent shows. It is, if you will, a bridge then.

A rather life-like donkey lies on his side, his entire body heaving with the effort to draw in breath. Still strapped on his back is a large black box. The black box is ubiquitous of the device that investigators at crime and accident scenes claim to search for, as though it contains all the answers to the what, how, and when questions that are raised in the aftermath of such an event. What this box contains is a mystery. The beast whose burden is it lies dying under its weight. The heaving breath is so labored it is almost to be wished that the animal would draw its last and die, finding release from the torturous effort of living.

It is a sad finale of the group of artworks, a silence of distress. What more emotion can be achieved, having gone full circle from fear to hope to death. Except perhaps the fortitude to progress from lessons learnt. On the one hand the answers are very simple but on the other impossible to reach, because of the complicated negotiations between personal ambition and collective good, and the clash between the desires of different collectives.

Deeksha Nath

January 2010