The Enigma of Departure

G.R. Iranna’s recent paintings are sites of struggle. Even a cursory glance at them fills the eye with a sense of tremendous dynamism, of volatility and ferment. A closer look reveals a series of conflicts being played out on the picture surface: between a colour and its neighbor; between figure and pigment; between the organic and the technological.

These paintings on canvas and tarpaulin represent a significant departure from Iranna’s previous works, an attempt, perhaps, to escape the potential prison of an established style. The large, central figure common in the artist’s early paintings appears only twice in the current crop. And, though Iranna continues to employ repeated motifs to provide his work with a sense of stability, such motifs now tend to be forms rather than figures.

To understand the nature of the change in Iranna’s art, if one has interpreted it accurately, it would help to examine its art-historical underpinnings. Iranna’s painting has always been far removed from the dominant, post-modern spirit of our time, utilizing, instead, the romantic, symbolist and modernist heritage of contemporary art. The word spirit needs to be stressed in the previous sentence because, inevitably, the style of Iranna’s paintings shows certain commonalities with art that is easy to classify under the postmodern rubric. But an analysis of the underpinnings of an artist’s work is more profitably aimed at the spirit of the work than on a few superficial stylistic features, which is why it is relevant to discuss Romantic and modernist ideas which may, in another context, seem anachronistic.

The modernist preoccupation with originality, with making it new, is certainly one strand that feeds into Iranna’s current work. But, insofar as ‘making it new’ involves a change of form, the modernist imperative comes into conflict with the Romantic aesthetic. The Romantics overturned the classical idea of form as ornament and established a counter-claim that form is, in fact, indivisible from the content of a work. They went even further than this, and implied that form is also intimately connected to the artist’s vision. In other words, to be original in the modernist sense, artists must strive to reinvent their style, but this very effort could call into question the integrity of their vision from a Romantic perspective.

There is a third strand to be added to the romantic and modernist one, that of contemporary expectation, the contemporary market if you will. A solo show represents the fruit of an artist’s development, as it were, something that is ripe, finished, ready for picking (or picking on in some cases). If we combine the three strands of which I have spoken – that of modernist originality, romantic form and contemporary expectation – we conclude that an artist like Iranna must, in this exhibition, stick to his vision, while departing significantly from it. And it is not enough for him to depart, he must also arrive at a new destination.

To return to the first contention in this essay, that Iranna’s new paintings are sites of struggle, one can now assert that the conflicts that we see in the work – colour against colour, figure against pigment, nature against technology – mirror the effort to fulfill the seemingly contradictory demands placed upon the artist. Having said this one quickly wants to add a rider to the proposition in order to avoid associations with pessimistic habits of thought (vulgar Marxist or Foucauldian) which allow the individual little or no agency. The demands one speaks of are demands that the artist has, to an extent, placed upon himself. They are demands that he is aware of at some level, demands that he may accept as a challenge.

Iranna has certainly accepted the challenge of re-forming his art. He has chosen to move in the direction of abstraction, of pure painterliness. This is a startling choice at a time when the figurative and conceptual have acquired a hegemonic position across the globe. But the artist has not arrived at an abstractionist position. It is unclear whether he will ever reach that state. There are still strong figurative and symbolic elements in his work. What we are presented with (confronted with) is a journey without any clearly implied destination.

In recent years the idea of a journey has been itself romanticized by a mindset that privileges experiences over discoveries, seeking over finding. One has no desire to fish in such mystical waters. But it is surely true that a chronicle of a voyage can be as intriguing as a description of newly discovered territories: each has its own singular pleasures.

What such a chronicle reveals is the perils faced by traveler, and Iranna’s paintings, to conclude the parallel, reveal the great risks he has taken in choosing this path at a time when viewers were still familiarising themselves with his previous work. Consider, for instance, the incongruity of a gentle figure holding a drooping lotus, reclining on a bed of springs, like Bheeshma reclining on a bed of arrows. This reclining figure is set in a field of flowers reminiscent of Monet’s Water Lilies. The relationship with the Water Lilies runs deeper than surface appearance, to the manner in which Iranna’s painting plays with our sense of gravity. In two other works the artist appears to nod towards neo-tantric painters like Biren De and Viswanathan while simultaneously questioning the harmonizing impulse of neo-tantrism. And in yet another canvas Iranna goes psychedelic, laying bands of bright colour over a sentimental picture of a baby in a bathtub. It is apparent that the artist’s references are eclectic, he resists being tied down to a unitary manner of perceiving the world.

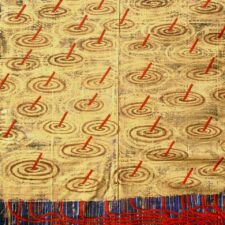

Iranna’s paintings are all heavily worked upon, built up with a multitude of layers. It is not enough for a thin black rod to break through the evenness of an effulgent yellow field: the rod itself carries within it a burning filament of red, and milky-white polyps protrude at regular intervals from the yellow ground which appears covered with flowers. And all this in a painting which appeals more to the viewer’s sense of simple harmony than any other work in the show. It sometimes seems that the artist wants to subdue the paintingto his will: even drips of paint, those symbols of the abdication of absolute power, are employed with unusual care, as if the artist wanted to achieve the impossible by charting a course for each drip. His efforts to yoke together disparate ideas, influences, images and colours demand this level of determination and they meet with a remarkably high degree of success. Iranna’s suite of paintings, besides being stimulating and evocative, leaves us looking forward to the next stage in the artist’s journey.

Freelance writer based in Mumbai.